By Clarissa Bezerra, Brasília, Brazil

As an educator and as a woman, I have had the privilege of having a very strong woman to look up to – my mother. Today, in my 39th birthday, after having spent most of my day by her side, I decided that it was time I wrote down a story she once told me about her life as a young and inexperienced teacher back in her hometown, a small and impoverished village by a river, called Cajari, in the heart of the state of Maranhão, northeastern region of Brazil. This was back in the early sixties, and my mom had just finished her studies, the then-called ‘Escola Normal’, which no longer exists, to become a teacher. Back then, it was the only choice a woman had to being someone’s wife and bearing children.

My grandmother Raimunda was my grandfather’s, Jerônimo, third wife. My mom was the first-born daughter of three siblings, but they had a whole bunch of other brothers and sisters from my grandpa’s first two unions. Having become an enthusiastic young teacher, my mom greatly contributed to the setting up of one of the first schools in her village, where she taught Portuguese, basic Math, and basic agricultural practices to students who were in their majority either as old as, or older than herself. She remembers the exhilarating feeling of standing in the front of the group in the very simple classroom. That was, she had always known, her true calling. She was a natural-born educator, taking after my grandma Dodoca, whom I will certainly write about in another post. Continue reading An education(al) anecdote from Brazil

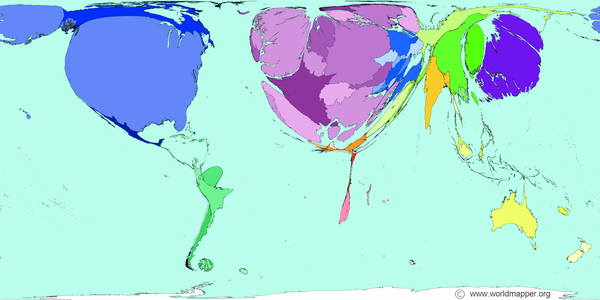

The world is getting far more connected, but not all connections are the same. Nor do connections automatically achieve the social, professional, and other purposes that the Internet is often credited for by those who have full and unhindered access to it. So, building a professional community, developing resources for it, and engaging its members from the ground up takes a lot of time, courage, and collaboration by one or more members who can stick to it through ups and downs, excitement and frustration.

The world is getting far more connected, but not all connections are the same. Nor do connections automatically achieve the social, professional, and other purposes that the Internet is often credited for by those who have full and unhindered access to it. So, building a professional community, developing resources for it, and engaging its members from the ground up takes a lot of time, courage, and collaboration by one or more members who can stick to it through ups and downs, excitement and frustration. In this blog post, we’d like to share the story of how we, a group of English language teachers in Nepal gradually built an online professional development community by the name of ELT Choutari. In a sense, this post is a detailed answer to the question that was asked by a colleague who commented on a

In this blog post, we’d like to share the story of how we, a group of English language teachers in Nepal gradually built an online professional development community by the name of ELT Choutari. In a sense, this post is a detailed answer to the question that was asked by a colleague who commented on a  ELT Choutari is probably the first English Language Teaching (ELT) blog-zine of its kind in South Asia. It was formed in 2009 by a group of dynamic ELT professionals of Nepal who felt the dire need of scholarly and professional engagement in the virtual world. To involve teachers across the country in professional development through online conversations, the team set up a blog, which was called ‘Nelta Choutari’ until recently. NELTA is the acronym for Nepal English Language Teachers’ Association where members of this informal group belong, and Choutari is a Nepali word meaning the space under/including a tree, the traditional public square where members of the community gather to share ideas and debate issues, tell stories to pass on or generate knowledge, solve problems, and sustain community.We changed the name to ELT Choutari in order to emphasize the group’s independence and informality and to be inclusive of the international scope of our readership—even as we remain grounded in Nepal and continue to share ideas and experiences of teaching/learning in our unique context.

ELT Choutari is probably the first English Language Teaching (ELT) blog-zine of its kind in South Asia. It was formed in 2009 by a group of dynamic ELT professionals of Nepal who felt the dire need of scholarly and professional engagement in the virtual world. To involve teachers across the country in professional development through online conversations, the team set up a blog, which was called ‘Nelta Choutari’ until recently. NELTA is the acronym for Nepal English Language Teachers’ Association where members of this informal group belong, and Choutari is a Nepali word meaning the space under/including a tree, the traditional public square where members of the community gather to share ideas and debate issues, tell stories to pass on or generate knowledge, solve problems, and sustain community.We changed the name to ELT Choutari in order to emphasize the group’s independence and informality and to be inclusive of the international scope of our readership—even as we remain grounded in Nepal and continue to share ideas and experiences of teaching/learning in our unique context.

Showing “

Showing “